Dave Elman Induktion

Dave Elman Induktion Dave Elman ist eine Kultfigur in der Hypnosewelt.Sein Induktionsverfahren hypnotisiert zuverlässig etwa

Wir schätzen Ihre Privatsphäre

Wir verwenden Cookies, um Ihr Surferlebnis zu verbessern, personalisierte Anzeigen oder Inhalte einzusetzen und unseren Datenverkehr zu analysieren. Wenn Sie auf „Alle akzeptieren" klicken, stimmen Sie der Anwendung von Cookies zu.

Wir verwenden Cookies, damit Sie effizient navigieren und bestimmte Funktionen ausführen können. Detaillierte Informationen zu allen Cookies finden Sie unten unter jeder Einwilligungskategorie.

Die als „notwendig" kategorisierten Cookies werden in Ihrem Browser gespeichert, da sie für die Aktivierung der grundlegenden Funktionalitäten der Website unerlässlich sind....

Notwendige Cookies sind für die Grundfunktionen der Website von entscheidender Bedeutung. Ohne sie kann die Website nicht in der vorgesehenen Weise funktionieren. Diese Cookies speichern keine personenbezogenen Daten.

Keine Cookies zum Anzeigen.

Funktionale Cookies unterstützen bei der Ausführung bestimmter Funktionen, z. B. beim Teilen des Inhalts der Website auf Social Media-Plattformen, beim Sammeln von Feedbacks und anderen Funktionen von Drittanbietern.

Keine Cookies zum Anzeigen.

Analyse-Cookies werden verwendet um zu verstehen, wie Besucher mit der Website interagieren. Diese Cookies dienen zu Aussagen über die Anzahl der Besucher, Absprungrate, Herkunft der Besucher usw.

Keine Cookies zum Anzeigen.

Leistungs-Cookies werden verwendet, um die wichtigsten Leistungsindizes der Website zu verstehen und zu analysieren. Dies trägt dazu bei, den Besuchern ein besseres Nutzererlebnis zu bieten.

Keine Cookies zum Anzeigen.

Werbe-Cookies werden verwendet, um Besuchern auf der Grundlage der von ihnen zuvor besuchten Seiten maßgeschneiderte Werbung zu liefern und die Wirksamkeit von Werbekampagne nzu analysieren.

Keine Cookies zum Anzeigen.

Wir unterstützen sowohl Anfänger als auch Profis, mit den besten Tools. Hier findest du alles zu Hypnose-Ausbildungen und Hypnose-Fortbildungen.

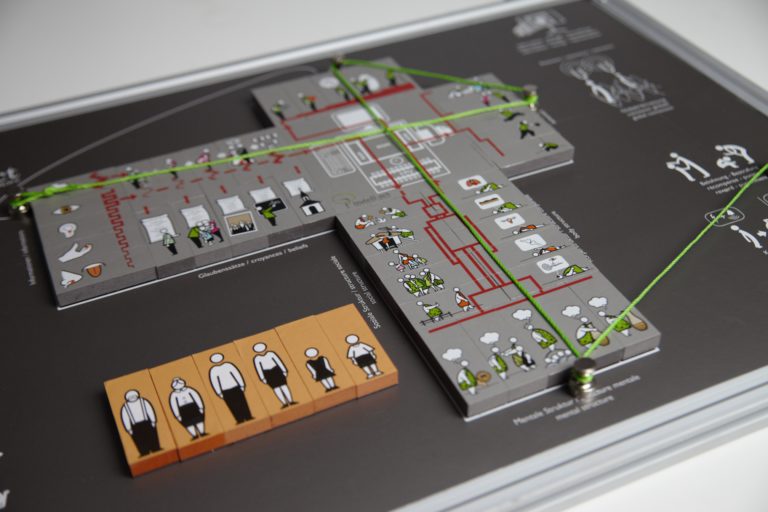

Hypnosis Institute ist das einzige Unternehmen Weltweit, bei dem das Life Puzzle Pro zur Ausbildung gehört.

Das Hypnosis Institute mit Sitz in Luxemburg ist die ideale Wahl für alle, die eine fundierte Ausbildung suchen, um die Vorteile von Hypnose und Selbsthypnose zu entdecken. Ob du Anfänger oder Hypnoseprofi bist, wir unterstützen unsere Teilnehmer mit den besten Werkzeugen und Ressourcen, um deren Hypnosefähigkeiten zu verbessern.

Als weltweit einzige Organisation, welche das "Life Puzzle Pro" in ihre Ausbildung integriert, bietet das Hypnosis Institute eine unübertroffene Erfahrung in der Hypnoseausbildung in ganz Europa. Wir bieten eine Vielzahl von Hypnose-Ausbildungsprogrammen für Anfänger und Profis an, darunter grundlegende Hypnose-Ausbildungen, fortlaufende Hypnose-Ausbildungen und Spezialseminare für erfahrene Anwender.

Unser Team aus erfahrenen Ausbildern ist bestrebt, ihr ganzes Wissen Wissen und die besten Techniken zu vermitteln, um Hypnose erfolgreich zu praktizieren. Wir stellen dir alles zur Verfügung, was du brauchst, um ein Hypnoseexperte zu werden, einschließlich bewährter Verfahren, praktischer Tipps und Trainingsübungen zur Verbesserung deiner Fähigkeiten.

Das Hypnosis Institute ist bestrebt, seinen Teilnehmern zu helfen, die Vorteile der Hypnose zur Verbesserung ihres Lebens zu entdecken. Wir glauben, dass jeder Mensch es verdient, Zugang zu Werkzeugen und Ressourcen zu haben, um geistiges und emotionales Wohlbefinden zu erreichen. Deshalb unterstützen wir Anfänger und Profis mit den besten Hypnosekursen, die in der Region und über Luxemburg hinaus verfügbar sind.

Kurz gesagt: Wenn du nach einer erstklassigen Hypnoseausbildung suchst, ist das Hypnosis Institute die einzige Organisation weltweit, die dir die Werkzeuge und Ressourcen zur Verbesserung deiner Hypnosefähigkeiten bietet.

Dave Elman Induktion Dave Elman ist eine Kultfigur in der Hypnosewelt.Sein Induktionsverfahren hypnotisiert zuverlässig etwa

Einführungskurs in Hypnose – Gratiskurs Mit diesem gratis Kurs bekommst du einen Einblick in Hypnose

Selbsthypnose Unser Selbsthypnosekurs ist eine großartige Möglichkeit, um die Kunst der Selbstbeeinflussung zu erlernen. In

Hypnose Basiskurs – Lernen Sie das Grund-Wissen und die Basis -Techniken der Hypnose Bei der

Hypnose – Masterkurs Bei der Hypnosis Master Class handelt es sich um eine Komplett-Ausbildung. Hier

Life Puzzle Pro 80% des Erfolges einer Therapie oder / und Coaching liegen bekanntlich im

Medical Hypnosis Basics Mit Abschluss der Ausbildung und bestandenem Test, haben Sie die Möglichkeit, sich

Notfall-Hypnose Es ist bekannt, dass sich Notfallpatienten, sei dies bei einem Unfall als selbst betroffene

Regression Altersregression in der Therapie wird auch als hypnotische Altersregression bezeichnet. Dies ist eine Hypnosetechnik,

Hier findest du die für dich und dein Thema angepasste und professionelle Unterstützung.

Wir bieten dir Maßgeschneiderte Konzepte. Finde heraus, was am besten zu dir passt!

Unsere hybride Hypnoseausbildung bietet optimales Lernen durch einen durchgehenden Teil. Es handelt sich nicht um einen einfachen Online-Kurs, sondern um eine komplette Live-Hypnoseausbildung. Wir bieten dir eine Hypnoseausbildung von höchster Qualität, damit du die Techniken der Hypnose beherrschen kannst.

Die Plattform von .Hypnosis Institute Luxemburg

Unsere Lernplattform ermöglicht dir einen einfachen Zugang zu allen Kursinhalten, wo immer du dich befindest. Egal, ob du einen PC, Laptop, Tablet oder ein Mobiltelefon verwendest, du kannst unterwegs flexibel und bequem lernen. Mache mit bei unserem Lernprogramm für eine moderne, auf deine Bedürfnisse zugeschnittene Lernerfahrung.

Wir bieten eine Vielzahl von Lernmethoden an, damit du dir durch Hypnose Luxemburg das nötige Wissen aneignen kannst. Zu den Lernmitteln gehören Videotutorials, fundierter theoretischer Unterricht, praktische Übungen und Zwischentests, um deinen Fortschritt zu messen. Schließe dich uns an, um von einem umfassenden und effektiven Lernprozess zu profitieren.

Unser Lernprogramm umfasst eine persönliche Betreuung und Supervision, um deinen Erfolg zu gewährleisten. Wenn du zusätzliche Unterstützung benötigst, stehen wir dir bei jedem Schritt auf deiner Lernreise zur Seite. Trete unserer Hypnose-Luxemburg-Lerngemeinschaft bei, um persönliche Unterstützung und die Begleitung zu erhalten, die du brauchst, um deine Ziele zu erreichen

Werde Teil eines weltweiten Teams und einer der besten Hypnose-Lernplattformen im Internet. Verdiene Geld mit dem was dir Spass macht.

Melde dich an und erhalte inspirierende Artikel, Hypnosetechniken und Tipps, wie Du dein Leben verbessern kannst.

Melde dich an und erhalte inspirierende Artikel, Hypnosetechniken und Tipps, wie Du dein Leben verbessern kannst.

Melde dich an und erhalte inspirierende Artikel, Hypnosetechniken und Tipps, wie Du dein Leben verbessern kannst.