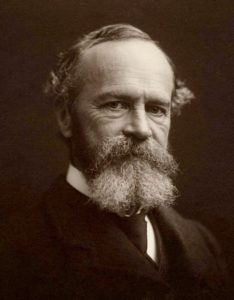

William James

William James (* January 11, 1842 in New York; † August 26, 1910 in Chocorua New Hampshire) was an American psychologist and philosopher. From 1876 to 1907 he was Professor of Psychology and Philosophy at Havard University. James is regarded both as the founder of psychology in the USA and as one of the most important representatives of philosophical pragmatism.

James is regarded as the founder of American psychology as a science. The introduction of the psychology department at US universities can be traced back to him. His psychological theories anticipated the basic ideas of Gestalt psychology and behaviorism and are an important foundation of the psychology of religion.

James’ main innovation is that he conceived of psychology in scientific terms and established a connection between states of consciousness and brain states in his theory. James considered the body and mind to belong together as parts of a unified organism. The contrast between body and soul, as it had been treated in the previous association psychology, was thus abolished and replaced by a psychophysical functionalism. James also practiced hypnosis himself; he examined and treated patients under hypnosis (account in: 1896 b, 73 ff).

In 1889, he took part in the 1st Congress of Experimental and Therapeutic Hypnosis in Paris (August 8-12), which was also attended by Freud and at which the dispute between Bernheim and Janet over the (general or only specific) applicability of hypnosis was settled. Ellenberger (1970, 360)

William James’ “Stream of Consciousness” claims that James exerted great influence on Janet. In the “Principles” he quotes at length the clinical reports of Janet’s investigations with “multiple personalities”.

James is interested in the similarities between these pathological phenomena and everyday phenomena – forgetting, false memories, dreams. In all cases, it is about “memory”. “The possession of the same memories” is what creates the unity of the person in the first place.

“However much the adult may differ from the youth he once was, both can call the same childhood their own in retrospect” (1890, 352). “There is no other identity than that which can be experienced in the ‘stream’ of subjective consciousness. The sameness of the individual moments in the continuum of feelings constitutes the real and truly experienced “personal identity” that we feel. If the link breaks at any point, the experienced unity is lost. If someone wakes up one fine day, unable to remember even one of his earlier experiences, so that he has to start his biography all over again; or if he remembers only the bare facts in cold abstraction, as if they had happened at some time; or if, without such a loss of memory, all his habits have fallen away from him overnight, so that every organ, every movement has become alien to him as well as his thinking, then he feels that he is a different person. He denies his former self (me), gives himself a new name, does not identify his present life with any moment of his former one. Such cases are not uncommon in the field of psychiatry . . . ” (319).

For James, these pathological cases only showed the possibilities of our consciousness in an exaggerated way.

In 1896, in the “Lowell Lectures” on “Exceptional Mental States”, they serve him, like the French psychiatrists, as proof of the existence of the unconscious. Each of us has two simultaneously operating systems of intelligent consciousness, one above the threshold of “awareness” and one below, with separate characteristics of their own (1896 b).

However, the “unconscious” is only an intermediate link in James’ theoretical development, which is not systematically developed further. He is closer to the idea of connection, of coherence (of consciousness). In “Varieties” he refers (again) explicitly to F. W. H. Myers’ concept of “subliminal consciousness” (1892), which he understands as “the – subconscious – continuation of our conscious life”, the “background against which our conscious being stands out in relief” (467 1 ).

In contrast to Freud, for James the unconscious was a “personal unconscious”, bound to the experience of the individual, even if it was no longer accessible to him. Our normal consciousness “is but a small drop out of the great ocean of possible human consciousness, of the limits of which we have no idea” (1898, 322). In the “alternate personalities”, dimensions of those further realms are expressed that are not normally accessible to waking consciousness. They can even be superior to them. “In such cases, where the secondary personality is superior to the primary, it seems reasonable to assume that the primary is the sick one. The word inhibition denotes their dullness and melancholy . . and the change (of personality, KJB) may be regarded as a removal of the inhibitions which have been preserved for years” (1890, 363). “We all know such inhibitions from times when we do not have our mental resources at our disposal” .

Hypnosis is a means of experimentally making accessible, or representing, these areas of experience, which normally only open up of their own accord in moments of inspiration and crisis. This was a large part of the fascination of hypnosis for contemporaries. Lears sees this as an expression of the “search for the authentic self” of the time, of the “longing for the reintegration of personality”, the attempt to work against the feeling of the dissolution of the self, the awareness that the identity of the ego had become problematic (117)

Source: The self-release of the ego in the metaphor of its dissolution: William James’ “Stream of Consciousness” Klaus-Jürgen Bruder